Kaneko Update 5 - What Is a Puzzle?

1/7/2016

...A miserable pile of-- Ah, nevermind!

But yes, during my latest ponderings of how to design some levels for Witch Doctor Kaneko, I had to ask myself that question: what exactly -is- a puzzle? How do I know if the level I've just made is a puzzle or not? And that's not even getting into GOOD puzzles! Well, here's what I came up with!

I think we can all agree, to start off, that a puzzle must have a solution. After all, the point of the game is to solve puzzles. So we must have a solution, but then, what is a solution? We can define a solution as a linear sequence of steps which completes the intended objective. For example, if our objective is to get to the flagpole at the far right end of the level, our solution would be "keep walking to the right" until we reach the flagpole.

But then, it's not enough to just have a solution, but to have MULTIPLE solutions -- some of which are incorrect. In other words, some solutions will be linear sequences of steps which fail to complete the intended objective. For example, "keep walking to the left" will fail to reach the flagpole, because we will never end up on the far right end of the level. And if we start thinking in forms of other puzzles -- such as the typical multiple choice question -- then we can formulate that a puzzle typically consists of one correct solution among many incorrect solutions.

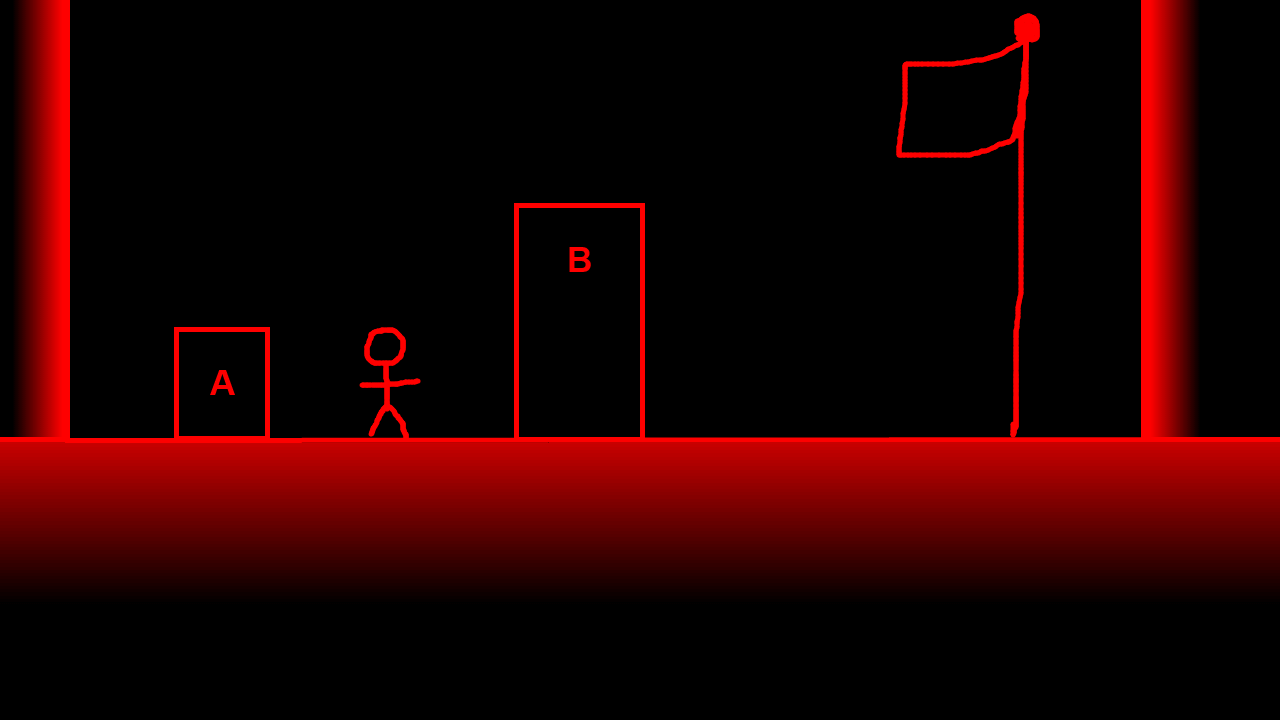

Is this the best definition we can come up with? Let's take another example, illustrated below:

Now, let's say the objective is to reach the flagpole at the right end of the level. Obviously, there is a very large block in our way. The apparent solution here would be to push the small block toward the large block, and then jump on each block until we reach the other side. This is because we cannot simply jump over the large block, but need to use the small block as a stepping stone. As a player in a video game, this solution would take only a few seconds to arrive at, and it would be fair to label this solution as "obvious." And by our definition of a puzzle, clearly some incorrect solutions exist (for example, pushing the small block all the way to the left and being unable to push it to the right anymore).

But is this truly a puzzle?! No! Intuitively speaking, nobody would call something like that a puzzle. There was no miraculous "a-ha moment" nor was there any intellectual challenge. Therefore, it seems we need to add another rule to our definition: the correct solution must not be obvious or apparent. That is, should we impulsively rush toward an answer, we'll likely find ourselves having picked the wrong solution. It becomes a requirement for us to stop and think a bit until we can realize which among the many solutions is the correct one.

How can we know which solution is correct? If the correct solution is not obvious , then there must be something -- some methodical deduction -- that we can use to determine it. Let's take an example of a puzzle from one of my favorite indie games, Braid.

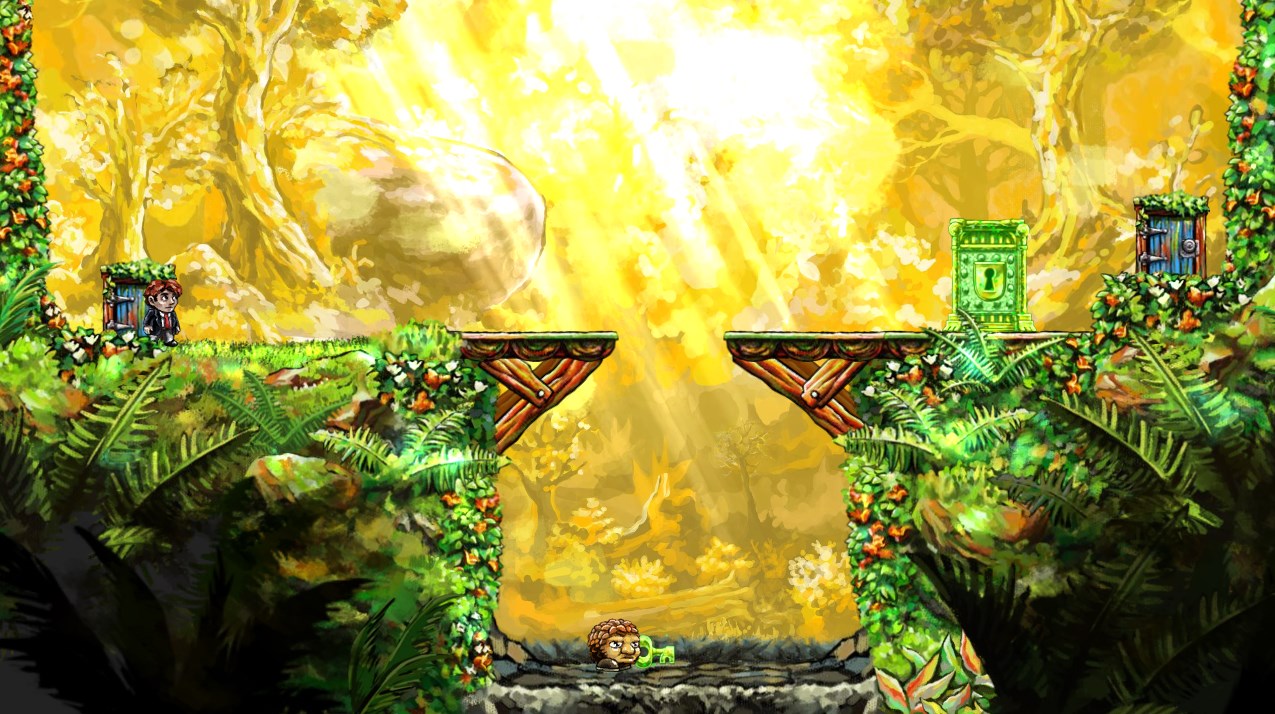

In this puzzle, the player is just trying to progress through the level, until they are stopped by a platform. This platform blocks their ladder, but luckily, they can flip the lever to move the platform. However, upon climbing the ladder, they realize that the moved platform now blocks their access to the puzzle piece. If they climb back down the ladder, the platform will be out of the way, but then the piece will also be out of reach. How do you reach the puzzle piece?

The answer relies in the game's core mechanic: time rewind! For the sake of not spoiling the game, I will not explain how to use it, but it's like this: you use the rewind mechanic in conjunction with the green objects (green = immune to time rewind) in order to get the world into the ideal state. In other words, the solution has nothing to do with anything I said in the question (the previous paragraph). It's entirely based upon something that the player intrinsically knew, and always had known -- a power which they always had access to and had always been available to them! They just had to think to use it, and to use it correctly!

Therefore, it would seem that the solution of a puzzle relies on an intrinsic gameplay mechanic which the player already knows and has always had available. In other words, no part of the solution is kept hidden from the player at any time. It is always there -- the player just needs to realize it! The environment -- the structure of the level -- only serves to change the way in which the player uses that game mechanic.

How can we teach the player to intrinsically know these mechanics? How can we be sure they are well-equipped with the tools needed to solve the puzzle? Let's look at an earlier puzzle from Braid:

By completing this puzzle, the player learns that green objects are immune to time-rewind. But it's not so much what the player learns, but how -- each step of the player is anticipated by the game. Watch closely: First, we know the goal is to get to the door on the other side of the pit. However, a lock is in our path, so we need a key. The key is being guarded by the monster in the pit, so we jump down into the pit and kill the monster. Now we have a key, but we can't get up out of the pit. So we rewind back in time to before we jumped into the pit -- and, wait a minute -- the key comes back with us! So we use the key to open the lock and proceed to the door.

The game effectively "predicted" all of the player's actions -- but how? Well, the future is easy to predict if there is no other option. In other words, the player had no choice but to perform each action, being led along a path that ended in a shocking twist. The player knows their goal is to get to the other side, the player knows that a lock is in the way, the player knows that keys open up locks, and the player knows that rewinding is the only way to get out of that pit. Rewinding time SHOULD have dropped the key -- that's what the player knew, too. That's what the player was expecting . But it wasn't what happened. Now the player learns something new: green objects are immune to the effects of rewinding time. Furthermore, by forcing this puzzle to be solved before moving on, we can guarantee that the player knows how this mechanic works. And we can use this mechanic for all future puzzles.

In short, effectively teaching a new mechanic to the player is like this: do the same thing you've been doing, but now something DIFFERENT happens! And once the player knows under which circumstances which things will happen, then we'll know that they can solve each puzzle we present to them. They will have the tools available, look at each situation, and realize how to use each one of those tools. And they will be able to spot which solution is the correct one, and then act upon their deduction and prove themselves right.

So, what is a puzzle? A puzzle contains at least one linear sequence of steps which accomplishes a particular goal, among a number of sequences which fail to accomplish said goal, and telling the difference between the two is not immediately obvious. However, the correct solution is intuitive, as it relies upon a gameplay mechanic that the player already knows about and always had the opportunity to use. Furthermore, the player can properly be taught said mechanics by limiting their actions down to one sequence, thus predicting each step in the sequence they will take, and then surprising them at the end. This ensures that the player knows the mechanic necessary to complete the puzzle, but is not hand-held through the process of determining how exactly the mechanic should be used.

Our definition, still, does not tell us what exactly a puzzle IS. Maybe, better worded: a puzzle is a problem with a non-obvious solution (among many false solutions) that has proper foreshadowing and is thus fair. So a puzzle is a fair test of choosing between right and wrong answers.

Well, no matter which way you put it, I think the longer definition is more useful from a developing standpoint. It lets me know HOW to make my puzzles fair. And thankfully, it lets me know when my level designs are actually puzzles, and not just a step-by-step procedure of things. Some games pretend to be puzzles, but really, they're just very obvious step-by-step procedures! The more interesting your game mechanic, the more creative you can get with the way your environment reacts with it. And the player will need to think about the relation between the mechanic and the environment in order to realize the solution.

As a reward for reading this far, here's a fun GIF I made showing off some Witch Doctor Kaneko prototyping! Thanks for reading!